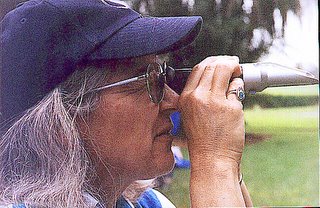

(left) Researcher Katy Watts peers through spectrometer to gauge the sugar content of grass at the Palm Beach Polo Club at the 2003 Palm Beach Laminitis Conference.

(left) Researcher Katy Watts peers through spectrometer to gauge the sugar content of grass at the Palm Beach Polo Club at the 2003 Palm Beach Laminitis Conference.CENTER, COLORADO—An expert in crop science, Katy Watts became frustrated when her own horses suffered from grass founder, the seasonal laminitis so common in many parts of the United States where the seasons change and grass pastures surge in growth in the spring and fall. Katy was unable to learn how or why the grass caused the terrible disease. She wondered about different types of grass. She wondered what happened to grass when it was dried for hay. She wondered about the effects of storage time and temperature. Did rain help or hurt the sugar content of hay?

Thanks to extensive collaboration between Katy and the Australian Equine Laminitis Research Unit at the University of Queensland, headed by researcher Chris Pollitt PhD, more and more information is becoming available about the role of non-structural carbohydrates in grass. In particular, the carbohydrate, or sugar-chain, called fructan has been implicated in laminitis.

Fructan is one of the energy engines in a blade of grass. When grass is stressed, it responds with an adrenalin-like surge of fructans to insure continued photosynthesis and survival. An example is a frosty evening, followed by a sunny morning. Katy has measured that grass on after-frost days is extremely high in fructan, which Pollitt in turn has shown can directly cause laminitis in large doses.

Katy is determined to educate American horse owners about the dangers of grazing horses on pastures planted and fertilized to fatten cattle. She would also like owners to be suspect of the carbohydrate content of their hay. High-fructan grasses are exactly what is needed for rapid weight gain and milk production in cattle.

Keeping horses off pasture at high risk times—such as after frosty nights--is only the beginning for Katy Watts. She also studies hay, and has conducted a study to show that soaking rich hay for an hour before feeding will reduce the carbohydrate content by 30 percent and hence drastically reduce the danger to horses.

Katy Watts has publicized the responsibility of horse owners to have their hay tested to determine the carbohydrate content. Independent laboratories are springing up where a small baggie of hay can be analyzed for a small sum; an example is the new Equi-analytical Laboratories, a division of Dairy One labs in Ithaca, New York. Color, grass types, blossom counts, and age are not reliable indicators. Watts has determined that a safe level of sugar/starch in hay is 10 percent or less for horses.